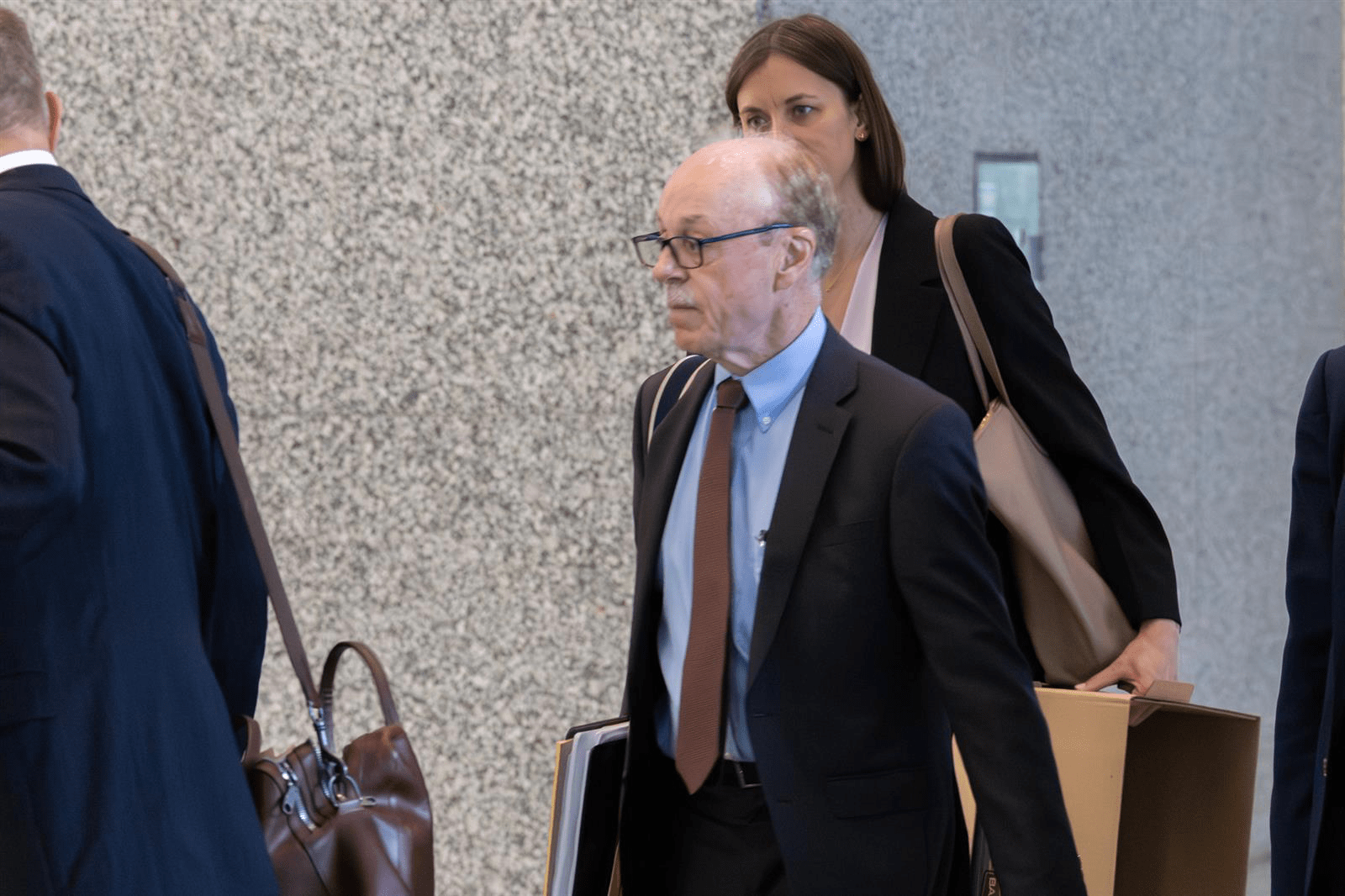

Tim Mapes, the former chief of staff for longtime Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan, exits the Dirksen Federal Courthouse in Chicago on Monday. He is standing trial for perjury and obstruction of justice. (Capitol News Illinois photo by Andrew Adams)

Tim Mapes’ perjury and obstruction of justice trial begins with opening statements

By HANNAH MEISEL

Capitol News Illinois

hmeisel@capitolnewsillinois.com

CHICAGO – Taking occasional notes – a habit hard-wired after more than 25 years as Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan’s chief of staff – Tim Mapes sat and listened to opening statements in his perjury and obstruction of justice trial in a federal courtroom on Wednesday.

Mapes allegedly lied to a grand jury in 2021 as it was investigating a bribery scheme in which Madigan allies were given jobs and contracts at electric utility Commonwealth Edison in exchange for legislative wins for ComEd. The utility’s former CEO and three ex-lobbyists – including Mike McClain, a close confidant of Madigan whose name came up hundreds of times during trial Wednesday – were convicted in May after a lengthy trial on those bribery charges. McClain and Madigan are both charged in a related bribery and racketeering case and face an April 2024 trial.

Mapes’ perjury charges center on whether he lied to a grand jury when asked about McClain’s role in Madigan’s organization. In his grand jury testimony, Mapes said he wasn’t aware of or didn’t recall any instances in which McClain was acting on Madigan’s behalf in the years after he officially retired from lobbying in late 2016.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Diane MacArthur began her opening statements by quoting Mapes himself.

“I always try to protect him,” Mapes allegedly said. “I mean, that’s my goal, it’s like in marriage. You’ve gotta have a spec— solid group around him…We’ll protect the boss.”

Mapes was under an immunity order when he appeared in front of the grand jury in early spring 2021. MacArthur pointed out that the chief federal judge in Chicago had warned Mapes twice – including directly before his hours of testimony – that not being truthful with the grand jury while under immunity would result in charges.

Even so, MacArthur said, Mapes “was not going to reveal anything about his close friends,” and in doing so, “jeopardized the integrity of the grand jury process.”

But Mapes’ attorney told a different story. In her opening statements, Katie Hill emphasized that Mapes’ relationship with Madigan was fundamentally different than the former speaker’s close and decadeslong friendship with McClain. While Madigan had entrusted Mapes with his role as chief of staff – in addition to companion jobs as clerk of the Illinois House and executive director of the Democratic Party – Hill sought to drive home that the relationship between the two was chiefly professional.

“Tim had very good reason to believe that when it came to McClain and Madigan, there were a lot of things he did not know,” Hill said. “Tim knew better than to presume he knew anything about those private conversations.”

Hill also tried to preempt the dozens of wiretapped phone calls the jury will hear during trial by telling them that Mapes’ indictment is based on his answers to just seven of the more than 650 questions he was asked during his grand jury testimony.

“You already know the government’s big punchline: All of this is on tape,” Hill said. “But as you consider that evidence ladies and gentlemen, consider that…they didn’t play him the tapes.”

The idea that Mapes was not given the opportunity to review any of the wiretapped calls or any other evidence – save for one document – during an early 2021 meeting with the FBI or his grand jury testimony is one the defense sprinkled throughout opening statements and while cross-examining the two witnesses put on the stand on Wednesday. Hill likened it to not being able to recall details from high school a decade after graduation unless prompted with items like a yearbook or notes passed in class.

Hill told the jury that when the defense makes its case later in trial, they’ll hear from a witness with expertise in how memory works, and how the ability to recall certain facts can be affected by being under stress. On that note, Hill said, Mapes was acutely aware of the high-stakes immunity order he was under, and therefore chose his answers to the grand jury carefully.

“Tim Mapes was told by the government that he’d be charged with a crime if he answered these questions wrong,” she said. “This was not the time to speculate.”

Wednesday also featured the first two witnesses of the trial, including former state Rep. Greg Harris, D-Chicago, who retired in January after serving the last four of his 16 years in office as the second-highest ranking member of the House. Harris served as House majority leader for Madigan’s final two years in office, and then continued the role after the speaker was ousted by his own party in 2021.

Harris’ testimony mostly gave the jury a basic understanding of how laws are made in Springfield and laid a foundation for how Madigan and Mapes ran the House. Earlier on Wednesday, Judge John Kness sided with the defense and blocked the government from playing a wiretapped call in which Harris had asked McClain advice about how he should approach Madigan to let him know he was interested in becoming majority leader in late 2018.

Asked earlier in his testimony why someone might approach McClain for advice even though he held no official role in state government, Harris said people “would assume he had the speaker’s ear.”

MacArthur asked Harris if McClain would also communicate information from Madigan – an important element for the government to prove at trial.

“I think sometimes, yes,” Harris said.

Lobbyist Tom Cullen, a longtime Madigan staffer in the speaker’s “inner circle,” testified about McClain’s involvement in the state’s Democratic Party, particularly when it came to fundraising.

He also spoke to Mapes’ power in both his official government roles and as director of the state party.

“He ran the entire operation,” Cullen said. “He was in charge of everybody and everything.”

Cullen also described a close friendship with Mapes and said he was shocked when Mapes was forced to resign from all three of his roles in June 2018.

The jury will be shielded from the exact nature of Mapes’ departure, which came after an employee of the House Clerk’s office publicly accused him of sexual harassment. Assistant U.S. Attorney Julia Schwartz read a stipulation into the record on Wednesday that Mapes resigned amid allegations of “inappropriate workplace professionalism regarding Mr. Mapes,” but also said it “has no relevance” in this trial.

“I was devastated,” Cullen said when asked for his reaction to Mapes’ ouster. “I couldn’t believe it happened.”

When Schwartz asked Cullen why he was shocked, Cullen answered simply.

“Because he was a loyal, hard-working individual for the speaker,” he said.

Cullen’s name has come up in the feds’ wide-ranging Madigan investigation before; his lobbying firm has identified as an entity through which AT&T Illinois allegedly funneled payments to a former state representative for a little-to-no-work contract – charges added to Madigan’s and McClain’s case in a superseding indictment last fall. But none of that was broached while Cullen was on the witness stand on Wednesday, and Cullen testified that he had been given a “non-target letter” by the feds.

The trial continues at 9 a.m. Thursday.

Capitol News Illinois is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news service covering state government. It is distributed to hundreds of print and broadcast outlets statewide. It is funded primarily by the Illinois Press Foundation and the Robert R. McCormick Foundation, along with major contributions from the Illinois Broadcasters Foundation and Southern Illinois Editorial Association.